The System Only Worked Because It Was Pushed

The most surprising aspect of the trial of Ahmaud Arbery’s killers is not the verdict, but the fact that it happened at all.

By Adam Serwer

About the author: Adam Serwer is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he covers politics.

The men who killed Ahmaud Arbery will not get away with it. Yet the most surprising aspect of the trial is not the verdict, but the fact that the trial happened at all.

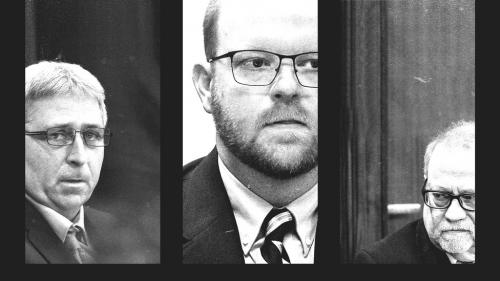

On Wednesday, a Georgia jury convicted Travis McMichael; his father, Gregory McMichael; and their friend William Bryan of felony offenses after the trio chased down and then shot Arbery in Brunswick, Georgia, in February of last year. The men claimed that they were attempting to make a “citizen’s arrest,” having suspected Arbery of being behind burglaries in the neighborhood, an accusation they had no evidence to support.

The three men were not even arrested until May. The district attorney, Jackie Johnson, recused herself from the case because the elder McMichael had been an investigator in her office. Johnson was later indicted for her actions in the Arbery case—allegedly preventing police from arresting the three men for Arbery’s killing. Video of the aftermath obtained by The Washington Post showed that Arbery was still alive when police first arrived but that “officers did not immediately tend to him and showed little skepticism of the suspects’ accounts on the scene,” the Post reported.

Ibram X. Kendi: Who gets to be afraid in America?

George Barnhill, who took over the case from Johnson, claimed the men had simply acted in self-defense when they chased down the unarmed Arbery, because “at the point Arbery grabbed the shotgun, under Georgia Law, [Travis] McMichael was allowed to use deadly force to protect himself.” In this view of the law, Arbery was at fault for his own death by defending himself from three men with guns who followed him in a truck and attempted to cut off his escape. Barnhill also recused himself—but only after Arbery’s mother complained that he, like Johnson, had also worked with McMichael.

It took video of the shooting going viral, in May of last year, for the men to be arrested. The clip showing Arbery’s death became public a few weeks before the release of the video showing George Floyd being murdered by a police officer. In retrospect, the two share a disturbing connection: The videos contradicted the statements of local authorities that both Floyd and Arbery were responsible for their own deaths. Without the video evidence—and the national protest, outrage, and scrutiny they sparked—neither man’s killers would have seen the inside of a courtroom. It took a series of extraordinary events to force the system to regard their deaths as crimes worth investigating.

The trial itself also proved illuminating. After Al Sharpton showed up in the gallery, Kevin Gough, one of the defense attorneys, said, “We don’t want any more Black pastors coming in here.” Last week, Gough complained about the public atmosphere surrounding the case against his clients, three white men who shot an unarmed Black man. “This is what a public lynching looks like in the 21st century,” he said. In her closing arguments, the defense attorney Laura Hogue told the jury, “Turning Ahmaud Arbery into a victim after the choices that he made does not reflect the reality of what brought Ahmaud Arbery to Satilla Shores in his khaki shorts with no socks to cover his long, dirty toenails.”

Defense attorneys are morally obliged to do their best to work the levers of the criminal-justice system on behalf of their clients. That said, it is notable that the defense team believed this approach was the one that offered their clients the best chance of beating the charges.

The defense successfully struck all but one Black juror from the pool. The team argued that the three men were executing a “citizen’s arrest” under a Georgia law that has since been changed, and insisted that McMichael had acted in self-defense against Arbery. “It was obvious that he was attacking me, that if he would’ve got the shotgun from me, then it was a life-or-death situation,” the younger McMichael testified. “And I’m gonna have to stop him from doing this, so I shot.”

If it sounds ridiculous to say that chasing someone down while armed is an act of self-defense, and then to claim you had to shoot the person you were chasing, because they tried to defend themselves, recall that this was precisely the conclusion the local authorities initially reached.

The jury ultimately found the defense’s arguments unpersuasive, and the evidence against the defendants overwhelming. But had it been up to the folks in charge in Glynn County, the jury never would have seen that evidence. To say the system worked in this case is like saying your car made it home—after your entire family had to get out and push it miles down a dirt road.