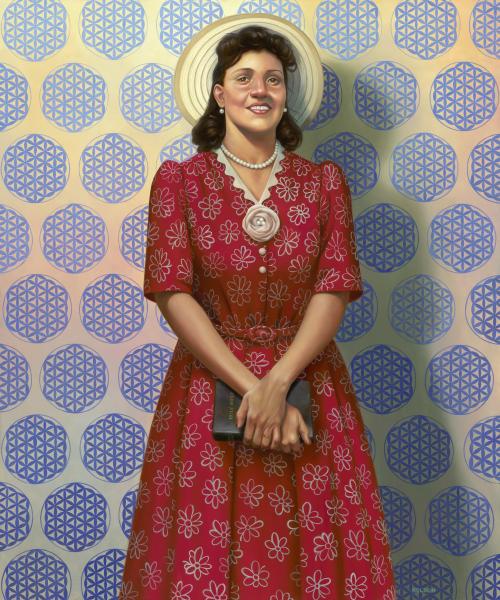

When Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital with cervical cancer in 1951, a researcher took cells from her tumor and discovered that, unlike other human cells, they survived and continued to replicate in the lab. HeLa cells, as they’re known, have since been sold all over the world, allowing countless researchers and companies to benefit. They’ve contributed to two Nobel prizes, the development of polio and HPV vaccines, cancer treatments, and AIDS research. A Black woman’s cells, taken without her consent or knowledge, transformed science.

Last week, two labs announced they would make the first donations in recognition of how they’ve profited from Lacks’ cells. But some scientists are underwhelmed by the field’s overall response.

“The amount of money being discussed versus profits made is ludicrous,” says Arthur Caplan, head of medical ethics at New York University’s School of Medicine. “If this is reparations for past racist and class abuse it isn’t even a drop in the bucket. Pure symbolism and nothing more.”

Last week, life sciences company Abcam, based in the UK, donated an undisclosed amount to the Henrietta Lacks Foundation to support scholarships in science, technology, engineering, and math for Ms Lacks’ descendants, according to the Wall Street Journal. And Samara Reck-Peterson, an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and professor of cellular and molecular medicine and of biological sciences at the University of California San Diego, said her lab will donate $100 for every four cell lines created by manipulating the HeLa cells.

If every lab who benefited from HeLa cells made a donation, Dr Reck-Peterson told the Wall Street Journal, these small amounts would build up and have a significant impact. So far, though, thousands of other labs that profited from HeLa cells have failed to give anything back.

Lacks was largely unknown until her story was revealed by Rebecca Skloot in her 2010 book ‘The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.’ Skloot created the Henrietta Lacks Foundation to fund health insurance and scholarships for Lacks’ descendants, and told the Wall Street Journal she had hoped corporations using HeLa cells would donate. Instead, donations have so far mainly come from individuals.

The businesses that benefited from HeLa cells have a moral obligation to make reparations, even if they don’t give monetary donations, says Jaime Slaughter-Acey, professor of epidemiology and community health at the University of Minnesota. “There’s no amount of dollars that can completely repair the damage that was done,” she says. She believes institutions must acknowledge how they contributed to harm, and then provide resources—financial or otherwise—to address the wrongs. Those that don’t donate to the Henrietta Lacks foundation must find other means to make amends for the unethical research practices and structural racism that allowed Henrietta Lacks’ cells to become a staple of science without her or her family’s consent, she adds.

Nearly half a century since Lacks’ death, the majority of scientific institutions that benefit from her cells have failed to adequately respond, in her view. “The fact only two foundations stepped forward and we don’t know exactly how much the donations were is a bit insulting,” says Slaughter-Acey. “Do other companies and foundations think they did anything wrong? What is their role in trying to make right?”

Source: Quartz